Sudan's Drone War: 1,000 Attacks and Counting

How foreign powers and improvised weapons are turning a civil war into a testing ground for the future of conflict

Since April 2023, Sudan’s civil war has become one of the most drone-intensive conflicts in the world. Over 1,000 documented drone strikes have killed more than 2,600 people, yet this aerial war receives little international attention. An Al Jazeera investigation reveals how Sudan has combined sophisticated foreign weapons with makeshift local adaptations in ways that could define future conflicts.

Differing Drone Strategies

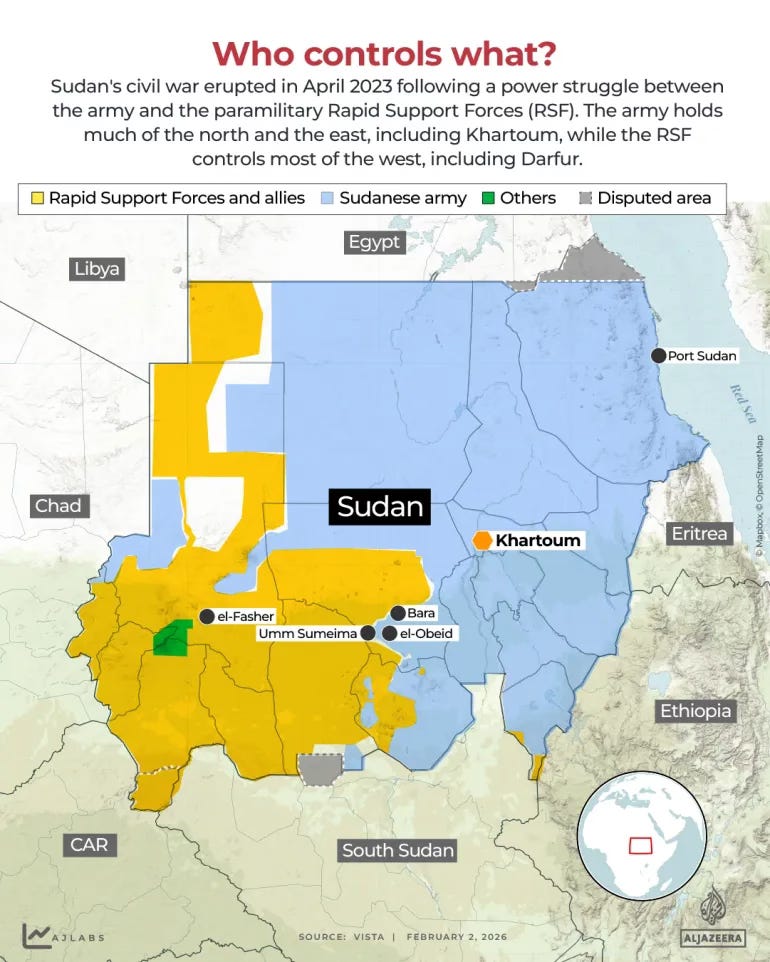

Sudan’s war involves the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) against the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a paramilitary group that evolved from the Janjaweed militias. Drones have leveled the playing field; although the RSF has no air force, its drones enable it to strike targets across the country.

The SAF relies on Iranian and Turkish drones like the Mohajer-6 and Bayraktar TB2, which are precision weapons designed for surveillance and targeted strikes. These drones can carry up to 40 kilograms of munitions and reach targets 2,000 kilometers away.

The RSF employs sophisticated Chinese Wing Loong II drones and Serbian VTOL systems, and also weaponizes commercial quadcopters. RSF fighters have modified off-the-shelf drones to drop mortar shells, turning easily available tech into weapons. According to Andreas Kreig, a security expert at King’s College London, this reflects the RSF’s “decentralized force with external supply options” where “approval chains are shorter, and the appetite for improvisation is higher.”

Foreign Powers Involvement

Both sides rely on international backers who ship weapons through a network of smuggling routes designed to circumvent embargoes.

The SAF receives support from Iran, Russia, Egypt, and Turkey, often using Eritrea and Port Sudan as entry points. Iran reportedly provides drones in exchange for a potential Red Sea naval base, while Russia switched its support from the RSF to the SAF in 2024, also seeking naval access.

The RSF’s main backer is the United Arab Emirates, despite Abu Dhabi’s denials. Cargo flights from the UAE land in eastern Chad at Amdjarass airstrip, just across the border from Darfur. Reuters documented at least 86 such flights carrying suspected weapons. From Chad, arms move overland into RSF-controlled territory. Other routes run through Somalia, Libya, and the Central African Republic.

Kreig explains the supply network: “The drones themselves rarely need to travel as complete aircraft. The most resilient model is modular transport: airframes, engines, datalinks, optics, batteries, ground control components, and munitions moving separately under commercial cover.”

This system is self-financing. The same routes that bring in drone parts carry gold and cash back out, creating a profitable cycle that sustains the war.

According to data from Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED), the five regions hit hardest by drone strikes are:

Khartoum: 440 attacks, 403 killed

North Kordofan: 122 attacks, 548 killed

North Darfur: 118 attacks, 577 killed

West Kordofan: 90 attacks, 567 killed

South Kordofan: 65 attacks, 396 killed

RSF drone attacks have killed over 780 people. SAF strikes have killed more than 1,800.

One attack stands out for its brutality. On December 4, 2025, the RSF launched three drones at a kindergarten and hospital in Kalogi, South Kordofan, killing more than 114 people, mostly children.

In May 2025, the RSF demonstrated its long-range capability by striking Port Sudan on the Red Sea, which was 1,600 kilometers from its western strongholds. The attack on Osman Digna Air Base involved 11 strategic drones, with reports suggesting foreign technicians helped assemble them at the al-Atrun base near Libya.

Why Sudan Matters

Sudan shows what happens when drone technology spreads beyond traditional militaries. The RSF proves that a non-state armed group can challenge a national army from the air without having an air force.

The conflict also reveals how easily drones can be sourced and adapted.

“Sudan is a strong predictor for future conflict in fragile states,” says Kreig, “because it shows how drones change the balance for militias, not just for states.”

Unlike Ukraine, where drones are mass-produced and systematically integrated into military operations, Sudan’s drone war is more chaotic and improvised. But that improvisation makes it more relevant to future conflicts in weak states where armed groups have external sponsors but limited infrastructure.

What Comes Next?

Kreig predicts more conflicts will feature “externally enabled procurement, contractor advice at the margins, improvised munitions and a mix of commercial and military-grade platforms tailored for disruption rather than precision.”

If a paramilitary force with no air force can use drones to strike targets nationwide, any armed group with foreign backing can do the same. The technology is available, the supply chains exist, and the incentives for external powers to provide support remain strong.

Thanks for reading Dronefare. Follow us on LinkedIn and subscribe to stay up-to-date on the latest developments in drone warfare.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and analysis.